How the Chord Search Feature Works

Imagine you walk into your kitchen to prepare a delicious meal. But you discover your fridge is almost empty.

There are only a few random ingredients here and there. And you now have to choose between:

- Going to the store.

- Going hungry.

But if you tell sites like SuperCook.com what's in your fridge, it’ll spit out a list of recipes you can cook right now.

There’s no need to buy extra food. You can start making dishes with the ingredients you already have.

Chord Genome works the exact same way – but for guitar music.

The platform indexes songs on popular guitar sites. And it organizes those tunes based on the chords they use.

Just search the chords you already know. And you'll discover thousands of songs you can start playing right now.

For example, a search of chords A, B, and C reveals:

- 3-chord songs that use A+B+C.

- 2-chord songs that use A+B or A+C or B+C.

- 1-chord songs that use A or B or C.

Sounds simple enough.

But it's a lot more complicated under the hood.

Let’s take a look.

Chord Search Logic and Standardization

There are many different ways to spell the same chord. This is especially true when pulling songs from user-submitted guitar websites.

Take chord A for example:

- Some people write “A.”

- Others use “AM.”

- “Amaj” is also popular.

- Don’t forget “Amajor.”

All of these spellings must be standardized behind the scenes to ensure you receive the largest number of playable results. When you search for songs that use Amaj, you also want to see tunes that use A, AM, Amajor, etc.

This cleaning process doesn’t just apply to the “major” family of chords. It also includes minor, augmented, diminished, 7th – the list goes on.

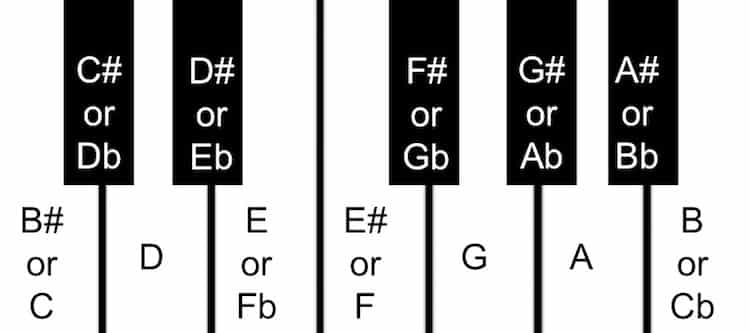

Then you have enharmonics.

These are notes that have the same pitch but completely different names – e.g. A# and Bb.

The keyboard below shows the most common enharmonic roots.

These enharmonic variations must also be standardized behind the scenes.

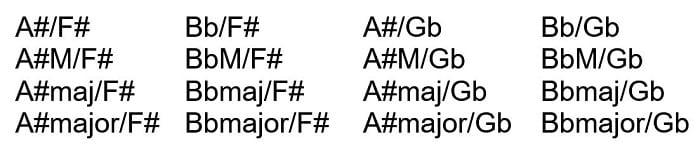

But there’s another layer of complexity – i.e. slash chords.

A slash chord (or “compound chord”) is when the root is no longer the lowest note. A good example is A#/F#.

There are so many different ways to spell that chord:

Most of these spelling variations will never appear in written music.

But if you map out all possible spellings for all known chords, the number exceeds 55,000. And Chord Genome must be flexible enough to accept all these spellings.

That’s the basic logic behind the platform’s Chord Search function.

But what about inversions?

Chord Search and Inversions

Just as there are many ways to spell a given chord, there are also many ways to finger each chord on the guitar fretboard.

Here are 12 variations for the Gmajor chord.

In sheet music, these inversions are usually written with Roman numerals. For example, G(ii) is the 2nd inversion of G.

Each inversion still uses the same notes (G, B, and D). But the order and placement change. And as a result, the sound of the chord changes as well.

However, Chord Genome ignores inversions by treating G, G(ii), and G(iii) equally.

Why?

There are a 2 reasons.

Reason 1: Learning the Basics

Inversions are important. But in the beginning, it makes more sense to learn the most basic version of each chord.

It’s similar to studying a new language.

You learn the word for “money” before branching into synonyms like “cash,” “green,” or “swag.”

These synonyms are all inversions of the same concept – i.e. money. And they add richness and complexity to the language.

But as an English student, it’s best to master the root word before learning any slang.

Reason 2: Maximum Playability

A tune that calls for G(ii) sounds better if you use that inversion. But the song is still playable with a standard G chord. And by ignoring inversions, Chord Genome can return way more results.

In fact, there are sometimes too many results.

To get around this, we’ve added filters – a beta feature that can help you sort through the mess.

Filtering Results by Genre and Decade

The Chord Genome database is massive, with roughly 350,000 songs. And it continues to grow.

That’s great news.

But the sheer number of results can quickly get overwhelming.

You can play nearly 4,000 songs using just 3 simple chords (G, C, and D). With 100 results per page, you’d have to click the “next” button 40 times to see every tune.

When you add a 4th chord, the number of playable songs jumps to 12,000+.

That’s a lot of clicking and scrolling.

And you won’t even know most of those songs.

But with Chord Genome's genre and decade filters, you can limit your search to:

- Rock tunes from the 1960s and 1970s.

Or

- 1950s Folk and Country songs.

Instead of 4,000 unfamiliar songs, you might see 300 tunes you actually know and like.

Pick the ones you want and start playing.

These filters are very useful. But they have certain limitations.

So be sure to read our article on: Using Genres and Decade Filters.

Not Sure What Chord to Practice Next?

Chord Genome shows you thousands of tunes you can play right now – using the guitar chords you already know.

But eventually, you’ll want to learn new chords so you can continue growing as a guitar player.

And that’s where the Next Best Chord (NBC) feature comes in.

No matter your skill level, this tool can tell you what single chord unlocks the most new playable songs in the database.

To learn how the NBC feature works, click here.

And if you haven't already, Sign Up Today to see how the platform really works.

Happy strumming.

What Songs Can I Play

with the Chords I Know?

To find out, use the Search tool below.

Type chords here or import from My Library